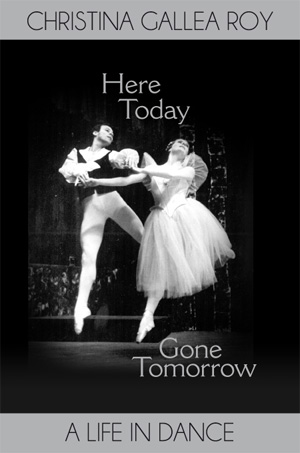

Here Today, Gone Tomorrow – A Life in Dance

A German dancer meets an Australian ballerina in an American ballet company, rehearsing in Germany, ahead of a tour in Spain. It seems an unlikely event, but it was a suitable introduction to a partnership where dance and travel were intrinsically interwoven. Alexander grew up in war torn Eastern Germany, surviving many hardships, and only by chance started out on a career as a dancer. He became a member of Germany’s leading ballet company, at the State Opera in Berlin, but was soon to grow restless enough to try his luck in the West. A chance meeting with Christina, who had made her way to Europe from Australia, where she had commenced a career as a ballet dancer at sixteen years of age, led to a professional and personal partnership. Both worked with international ballet companies and with famous teachers and choreographers before setting off on an independent path; firstly performing a duo concert programme throughout Europe and then, based in Paris, founding a small, itinerant ballet company, International Ballet Caravan. Alexander choreographed the ballets and both learned skills they had never dreamed of, – in administration, publicity, stage management and theatre design.

A German dancer meets an Australian ballerina in an American ballet company, rehearsing in Germany, ahead of a tour in Spain. It seems an unlikely event, but it was a suitable introduction to a partnership where dance and travel were intrinsically interwoven. Alexander grew up in war torn Eastern Germany, surviving many hardships, and only by chance started out on a career as a dancer. He became a member of Germany’s leading ballet company, at the State Opera in Berlin, but was soon to grow restless enough to try his luck in the West. A chance meeting with Christina, who had made her way to Europe from Australia, where she had commenced a career as a ballet dancer at sixteen years of age, led to a professional and personal partnership. Both worked with international ballet companies and with famous teachers and choreographers before setting off on an independent path; firstly performing a duo concert programme throughout Europe and then, based in Paris, founding a small, itinerant ballet company, International Ballet Caravan. Alexander choreographed the ballets and both learned skills they had never dreamed of, – in administration, publicity, stage management and theatre design.

A move to London meant a more permanent home and within ten years, the company, now known as Alexander Roy London Ballet Theatre, had become part of the British ballet scene. As well as performing in London and all over the UK, the company appeared in Paris, Berlin, Brussels, Geneva, and throughout Europe, even behind the Iron Curtain. Spreading its wings still further, they were soon travelling regularly to South East Asia, North and South America, and besides the capital cities such as New York, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Caracas, they performed as far afield as Sarawak and Alaska, Ecuador and Trinidad.

The aim was ‘independence’; free of restraints from managements and committees, to ignore tradition and hierarchy, and to exist without relying on subsidy and outside funding. Independence has its advantages and its pitfalls and obviously, there were many battles in order to survive, and to meet the standards to which they aspired. The books charts what was an extraordinary voyage, commencing with two dancers in an overloaded Volkswagen ‘beetle’, evolving to become an international ballet company performing to audiences throughout the world. It all took place during an exciting period of dance history and the book includes many details of dancers, teachers and choreographers many of whom have often been neglected, and whose contributions to this ephemeral art form are in danger of being lost. It also describes countries and cities visited in the days before international air travel became commonplace and before motorways criss-crossed Europe. This very individual contribution to 20th century dance is not only an unusual one, but possibly unique.

HERE TODAY, GONE TOMORROW – A Life in Dance was published in May 2012 and is available from all major UK bookshops, internet booksellers world-wide, including Amazon.co.ok

EXTRACT – HERE TODAY, GONE TOMORROW

STRETCHING OUR WINGS- 1974

The tour to South-East Asia was a year in the making but up to the very last it looked as if it might never happen. The British Council, an organisation somewhere between the Arts Council and the diplomatic service, and responsible for most of the national theatre and dance companies’ performances abroad, had recommended the travel agent. The tour required us to take ten people from London to Bangkok, and then on to Penang, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Hong Kong, Manila, Taipei and back to London, while the flights needed to fit into an already existing schedule of performances. It was also essential to find an airline with a ‘flexible’ policy towards a group travelling with a number of large trunks, containing all our costumes, props and belongings. The travel agent did not appear to have an office, so we had only been able to speak to him by phone, but the fares he offered were highly discounted, and much better than anything we had been able to find ourselves. Finally arrangements were made; he would hand over the tickets on the eve of our departure, in a pub in a back street behind Tottenham Court Road – and we should bring cash. The auspices were not good, but we had little choice. Sharing the thousands of pounds between us, Alexander and I arrived at 5.30 pm just when office workers poured out of the surrounding buildings, rushing into the underground station and the neighbouring pubs. In the crush of the appointed pub, a seriously obese young man with a highly flushed face and sweat stained shirt introduced himself and we exchanged packages. There was little point in attempting to check the huge bundle of tickets in the overcrowded, noisy pub and in any case, there was no time now to rectify any mistakes.

The next morning, we all gathered at the British Airways Terminal at Cromwell Road at five o’clock, bleary-eyed and already confused on a dark and wet November day. It was light by the time we changed planes in Paris, and travelling on a bright, clear day we could follow the flight path across Europe to the Mediterranean, and on through the Middle East, helped by the generosity of Air France, which in those days, offered excellent food at all too frequent intervals. The plane paused on the tip of Arabia, at Abu Dhabi, where I rushed to the open door to breathe in the exotically ‘foreign’ air of Arabia, marvelling at the star-filled sky. Then we were off to Delhi, where we stopped again, still imprisoned in the jumbo, while it was brushed and cleaned, loaded and unloaded, while one became aware of the warmth outside and the inevitability of it really staying warm. Following a night of fitful sleep, we arrived at Bangkok’s Don Muang Airport, after swooping low over the first sight of the lush jungle growth of Thailand and the tiny box-like houses on stilts skirting the ribbons of the many rivers. At the airport we were met by the local promoters, ex-pat British, and were escorted into Bangkok in a rather large, shaky bus. The first thing one notices in Thailand are the trucks; there are trucks everywhere- bearing down on our bus, overtaking intrepidly, swerving and diving around us like flights of playful swallows; shining silver-plated monsters, studded and almost jewelled, painted and gaudily decorated, daubed with fairy lights and showing glimpses of pin-up girls next to religious icons. The trucks are loaded, even overloaded, with sacks and baskets almost tumbling over the sides: fruits and coconuts as well as passengers hanging over the back or perched, precariously, on top of it all. Then one notices the water; in the country there are endless fields and streams of water, while in the city, all around us, filthy, muddy water, which splashed us as we rushed by in our rumbling 1940’s-model bus, and also splashed those crouching or sitting on the pavements, cooking, eating, selling and watching. Arriving at a pleasant hotel, we were offered a wonderful Thai buffet lunch of enticing salads and tropical fruits, a kaleidoscope of extraordinary new colours and smells and tastes. After lunch some of us ventured out of the air-conditioning into the heaviness of the heat outside where the eating was still going on. Everyone, it seemed, was cooking or eating or selling food. Women crouched over their charcoal burners on the pavements, concocting delicious looking dishes of meats and vegetables, salads and desserts; little stands served sizzling meat dishes and fresh fruit juices; the shops were jammed full of salted fish, fresh meat, most of it unidentifiable, fruit and vegetables, puddings and pastries. A great living feast was taking place among the exhaust-fumes, the flooded gutters, the noise, the smells and the heat. For most of us it was the first experience of an Asian country, and the first encounter with poverty on a scale we had never imagined, although by Asian standards, Bangkok was, even then, an almost westernised city.

The National Theatre is part of a large university complex,……..

©Christina Gallea Roy

*

EXTRACT – HERE TODAY, GONE TOMORROW

PARIS – A Turning Point

The most important of the Parisian dance studios were at the Salle Wacker, situated at 69 Rue de Douai, just off the Place Clichy. The street level was occupied by a piano show room packed with an assortment of rather dusty grand pianos. On the first floor there were more pianos scattered messily on the large landing, and facing one was the restaurant and the notice board – the Parisian ‘market place’ for dancers. Many of the best teachers in Paris had taught here since the 1920’s, and until 1960 the Russian ex-ballerina of the Maryinsky Ballet, Olga Preobrajenska was the ‘star’ teacher, having trained generations of dancers, creating many of the most famous. Retiring finally when she was nearly ninety years old, ‘Preo’ was loyally supported both personally and financially by those dancers and ex-dancers until her death a couple of years later. Her former colleagues from the Imperial Maryinsky Ballet in Saint Petersburg, who also settled in Paris to teach, were Lubov Egorova and Mathilde Kschessinkaya, both of whom married Russian princes, and who presumably managed to bring at least some of their wealth from revolutionary Russia with them. Kschessinskaya, a former mistress of Tsar Nicholai, was the undoubted star dancer of the trio, both beautiful and talented, leaving Russia even earlier to perform both at the Paris Opéra Ballet and with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes

Among those teaching at Salle Wacker when we arrived in Paris was Nora Kiss, her aunt, Madame Roussanne, and Victor Gsovsky. The restaurant with its long bar was a traditional meeting place for dancers, in and out of work, as it was for ballet masters, company directors and agents. If you were looking for a job, you could be lucky by the end of the day; you would have found one, either by attending a class, searching the notice board or listening into the latest news over a coffee at the bar. Ballet classes took place all day long, with Madame Nora giving three classes daily as well as pas de deux classes and private lessons. Before continuing further upstairs one was interrogated by a severe looking woman behind a polished wooden counter who needed to be convinced that one was attending a class, and not attempting to use an empty studio without paying. The building was a warren of studios, tiny ones for singers and musicians, the dance studios of varying shapes and sizes. The staircase wound up the centre of the building with lavatories built into the walls between floors. Without any space inside, and lacking a landing outside, it was a battle to flush the traditional ‘hole in the ground’ and exit before soaking one’s feet and losing one’s belongings tumbling back down the stairs. Madame Nora’s main professional class was at midday and was packed with ‘étoiles” from the Paris Opera Ballet, the many free-lance dancers in Paris, as well as visitors from abroad. Madame Nora must have left her native Georgia at an early age as she had studied in Paris, notably with Volonine, Anna Pavlova’s favourite partner. She had danced with various Ballets Russes companies, including that directed by George Balanchine, after Diaghilev’s death. She appeared to speak faultless Russian, French, Italian, German and English, to know everyone in the dance world, and was always au fait with all the latest developments. She was also an indefatigable learner, studying Rudolf Nureyev in performance, the details of his tours en l’air, the speed of his arms in a pirouette or his landing after a jump. She would watch gymnasts, skaters or even horses on TV for new insights into the technical problems of jumping or landing or balancing, enticing us to try them out in class the following day. In today’s ballet classes, many teachers have abandoned giving corrections; dancers prefer to cover themselves in layers of bulky practice clothing, disguising weak feet, or a bad posture, unwilling to surrender to the scrutiny of a teacher. In Paris, we had little choice: Madame Nora would make fun of a Paris Opéra Ballet star, like Attilo Labis, thumping the colossus of a man firmly on the back, until he did as she wished, or chase an unwilling Milorad Miskovitch out of the changing room following a heated argument. Her classes were long, a good two hours, but basically very simple. Rather than give choreographically interesting enchaînements, she taught how to turn better, how to jump higher and how to improve all of one’s skills. Her method was unconventional, and she would surprise one by coming up to one at the barre, while attempting a complicated exercise such as a series of double frappés, interspersed with pliés and relevés, as well as changes of arms and head positions, demanding to know where one was living or if one had seen a certain film or performance. It was a ploy, of course, to stop tension, to make one work without straining the head and shoulders, while using all the necessary strength in the feet and legs. Another ‘trick’ was to make one sing along with the music while exercising, which, of course, is highly effective at making one relax.

At lunchtime she would take up her position at a small table in the first floor restaurant immediately in front of the main studio entrance. From there she could keep an eye on everyone coming or going, and would challenge any unfortunate who attempted to creep past on their way to another class or audition. She often demanded to know where one had been the previous day, what time one had gone to bed, even what one had eaten the previous evening, and she had suggestions for improvements on all matters. She did also often have serious rows with many of her pupils, and the Paris studios were full of one time followers of Madame Nora who either did not dare go back to her class or who had sworn never to do so again. It is said that the only time Madame Nora missed a day of classes was when she joined the huge funeral cortege for Edith Piaf which filled the streets of Paris, and whom, she did physically resemble.

Another of our favourite teachers was Serge Peretti …….

©Christina Gallea Roy